What was the geocentric theory?

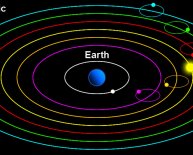

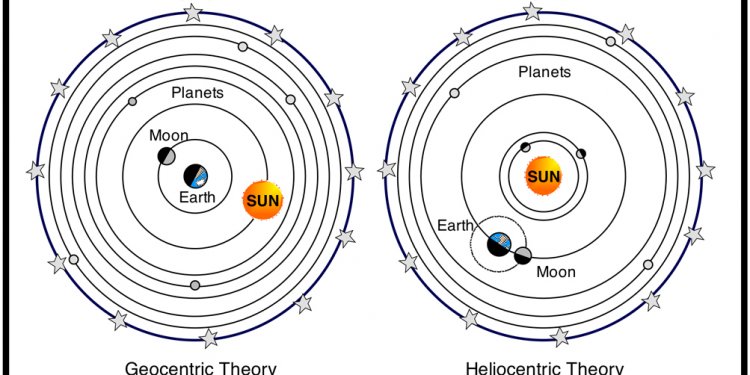

Rejected by modern science, the geocentric theory (in Greek, ge means earth), which maintained that was the center of the universe, dominated ancient and medieval science. It seemed evident to early astronomers that the rest of the universe moved about a stable, motionless Earth. The, , planets, and stars could be seen moving about Earth along circular paths day after day. It appeared reasonable to assume that Earth was stationary, for nothing seemed to make it move. Furthermore, the fact that objects fall toward Earth provided what was perceived as support for the geocentric theory. Finally, geocentrism was in accordance with the theocentric (God-centered) world view, dominant in in the Middle Ages, when science was a subfield of theology.

Rejected by modern science, the geocentric theory (in Greek, ge means earth), which maintained that was the center of the universe, dominated ancient and medieval science. It seemed evident to early astronomers that the rest of the universe moved about a stable, motionless Earth. The, , planets, and stars could be seen moving about Earth along circular paths day after day. It appeared reasonable to assume that Earth was stationary, for nothing seemed to make it move. Furthermore, the fact that objects fall toward Earth provided what was perceived as support for the geocentric theory. Finally, geocentrism was in accordance with the theocentric (God-centered) world view, dominant in in the Middle Ages, when science was a subfield of theology.

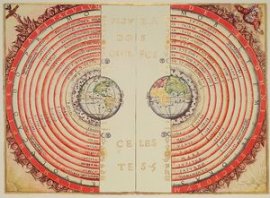

The geocentric model created by Greek astronomers assumed that the celestial bodies moving about the Earth followed perfectly circular paths. This was not a assumption: the was regarded by Greek mathematicians and philosophers as the perfect geometric figure and consequently the only one appropriate for celestial . However, as astronomers observed, the patterns of celestial motion were not constant. The Moon rose about an hour later from one day to the next, and its path across the sky changed from month to month. The Sun's path, too, changed with, and even the configuration of constellations changed from season to season.

These changes could be explained by the varying rates at which the celestial bodies revolved around the Earth. However, the planets (which got their name from the Greek word planetes, meaning wanderer and subject of error), behaved in ways that were difficult to explain. Sometimes, these wanderers showed retrograde motion—they seemed to stop and move in a reverse direction when viewed against the background of the distant constellations, or fixed stars, which did not move relative to one another.

To explain the motion of the planets, Greek astronomers, whose efforts culminated in the work of Claudius Ptolemy (c. 90-168 A.D.), devised complicated models in which planets moved along circles (epicycles) that were superimposed on circular orbits about the Earth. These geocentric models were able to explain, for example, why Mercury and never move more than 28° and 47° respectively from the Sun.