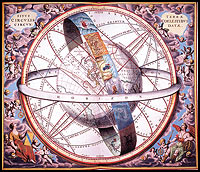

Galileo universe

Galileo vs. the Pope

Special to The Washington Post

On June 22, 1633, Galileo Galilei was put on trial at Inquisition headquarters in Rome. All of the magnificent power of the Roman Catholic Church seemed arrayed against the famous scientist. Under threat of torture, imprisonment and even burning at the stake, he was forced, on his knees, to "abjure, curse and detest" a lifetime of brilliant and dedicated thought and labor.

By then an old man of 69 who in his defense referred to his "pitiable state of bodily indisposition, " Galileo was charged with "vehement suspicion of heresy." He had to renounce "with sincere heart and unfeigned faith" his belief that the sun, not Earth, was the center of the universe and that Earth moved around the sun and not vice versa, as ecclesiastical teaching dictated.

Because he was willing to do this, at least verbally, the more serious of the threats remained only that. As one of his punishments, for example, he was to recite the seven penitential psalms once a week for three years. He also was placed under house arrest for the rest of his life.

Finally, his book, Dialogue on the Great World Systems, Ptolemaic and Copernican (1632), which lay at the heart of the trial, was added to the index of banned books, Index Librorum Prohibitorum, maintained by the Inquisition.

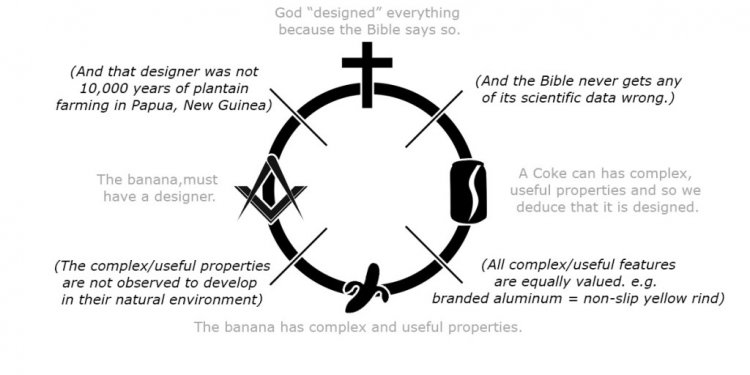

Ten cardinals sat in judgment of Galileo. Pope Urban VIII was not present in person, but he was there in spirit, for his personal feelings of anger and frustration were the driving force behind the extraordinary proceedings. Urban recognized just how seriously Galileo's new science challenged established church doctrine. Worse, Galileo had declared that the book of nature was written in the language of mathematics, not in biblical terms.

Cardinal Maffeo Barberini had taken the name Urban VIII in 1623 at age 55. Until then, he was, by all accounts, a warm, compassionate, intelligent human being and one of the few with whom Galileo felt that he could discuss his work intelligently.

Cardinal Maffeo Barberini had taken the name Urban VIII in 1623 at age 55. Until then, he was, by all accounts, a warm, compassionate, intelligent human being and one of the few with whom Galileo felt that he could discuss his work intelligently.

During one of Galileo's visits to Rome soon after Urban's election, the famous scientist was granted six audiences, each lasting more than an hour, an extraordinary allocation of the pope's time. In fact, it was largely because of Urban's election that Galileo began to think he could safely write the Dialogue.

Both men had been born and raised in Florence and attended the University of Pisa, where Galileo studied medicine and Urban took a law degree. As a cardinal, Barberini had even interceded on Galileo's behalf during a confrontation with church authorities in 1616 when Galileo had been warned that his support of the concept of a sun-centered universe could bring trouble.

By 1632, about 16 years after that foreboding event, Galileo was a widely known and respected scientist and the official astronomer and philosopher at the court of the grand duke of Tuscany.

After deciding to publish the Dialogue, Galileo had followed strict protocol. He had his book scrutinized by church censors and received the church's official imprimatur. He had clearly fooled all of the officials into thinking that his ideas were being presented only as hypotheses. He had almost gotten away with publishing a heretical work without provoking papal fury.

A Loyal Son

Galileo, however, was no scoffing atheist nor angry escapee from religion. He had attended Catholic school, both of his daughters had become nuns and, most important, he considered himself a loyal son of the church. He felt that he was trying to save, not hurt, the church. He was trying to prevent the church from having to defend a doctrine that he thought subject to disproof.

Galileo was far from the first to challenge authority.

In 1543, the Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus had proposed the heliocentric (sun-centered) system. A canon in the Polish Catholic Church, he had recognized the possibility of trouble and delayed publication for many years. It is likely that he far overestimated the impact of his writing, which turned out to be one of history's major unread works.

As long as the doctrine lay shrouded in Latin, just another long-winded academic treatise that few read or cared about, the church could safely ignore it. The book never made the index, a sure sign of impotence - at least not until 1616, when Galileo's support of the doctrine forced the church to recognize the fertility of Copernicus's revolutionary idea.

The traditional view had been codified about 150 A.D. by Ptolemy of Alexandria, an astronomer and geographer who put together an astronomical system to explain the apparent motion of the night sky. Ptolemy's solution was a system in which Earth was at rest in the center of the universe, with the moon, sun, planets and stars revolving around it, all embedded in a system of concentric, crystal spheres.