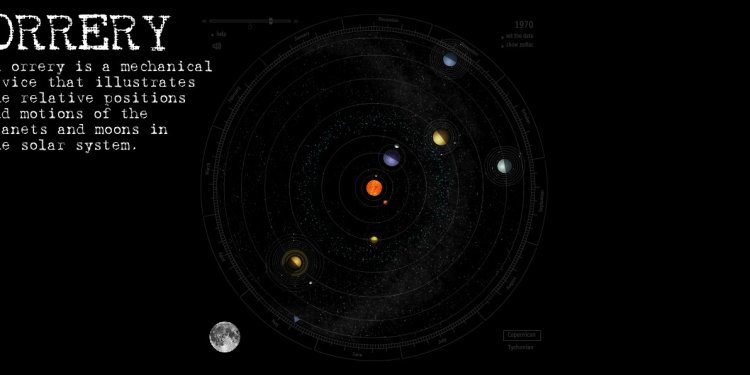

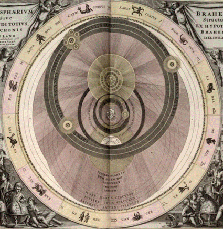

Earth-centered model

In 1543, Copernicus suggested the sun was at the center of the cosmos. However, it was centuries before a sun-centered model became widely accepted. The history of science is often thought of as a procession of discoveries and advances. This obscures the complex stories of how theories and models can compete and coexist over long periods of time. When the Copernican model eventually won out it had been so extensively refined that the name "Copernican" doesn't tell the whole story.

In 1543, Copernicus suggested the sun was at the center of the cosmos. However, it was centuries before a sun-centered model became widely accepted. The history of science is often thought of as a procession of discoveries and advances. This obscures the complex stories of how theories and models can compete and coexist over long periods of time. When the Copernican model eventually won out it had been so extensively refined that the name "Copernican" doesn't tell the whole story.

As evidence mounted in favor of a sun centered model, it remained one of many competing models for describing and explaining the heavens. By looking at how Tycho Brahe's model, the Copernican model and the Ptolemaic model were represented in the 17th and 18th centuries, we will see the long period of competition between these models.

Weighing Cosmological Models in 1651

When Jesuit astronomer, Giovanni Battista Riccioli published his Almagestrum Novum or "New Almagest" the title alone suggested the boldness of the project. This was to be a new and updated take on Ptolemy's Almagest. The book offered new insight into the state of thought about the cosmos in 17th century Europe.

The frontispiece to Almagestrum Novum illustrates Riccioli's evaluation of three models of the universe. Discarded at the bottom left of the image is the Ptolemaic model. In the center Urania, the muse of astronomy, weighs a variant of Tycho Brahe's revised Earth-centered model against Copernicus sun-centered model. Brahe's model, in which the planets orbit the sun and the sun orbits the Earth, beats out Copernicus model in this evaluation. From Riccioli's evaluation, the Earth-centered model of the cosmos was still the best choice.

The frontispiece to Almagestrum Novum illustrates Riccioli's evaluation of three models of the universe. Discarded at the bottom left of the image is the Ptolemaic model. In the center Urania, the muse of astronomy, weighs a variant of Tycho Brahe's revised Earth-centered model against Copernicus sun-centered model. Brahe's model, in which the planets orbit the sun and the sun orbits the Earth, beats out Copernicus model in this evaluation. From Riccioli's evaluation, the Earth-centered model of the cosmos was still the best choice.

In the book, Riccioli presents problems with the Ptolemaic, Copernican and Tychonic models and then offers a variant of Tycho Brahe's model which he believes slightly more correct. For him, it made the most sense to have Mercury, Venus and Mars orbit the sun but still have Jupiter and Saturn orbit the Earth.

One of Riccioli's arguments in favor of the Tychonic model was that since everything was created for humanity it simply made more sense that Earth would be at the center of creation. The argument about our place in the cosmos was a major philosophical issue that scientists, philosophers and theologians debated for centuries.