New Astronomy News

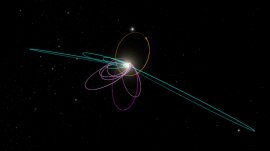

Caltech researchers have found evidence of a giant planet tracing a bizarre, highly elongated orbit in the outer solar system. The object, which the researchers have nicknamed Planet Nine, has a mass about 10 times that of Earth and orbits about 20 times farther from the sun on average than does Neptune (which orbits the sun at an average distance of 2.8 billion miles). In fact, it would take this new planet between 10, 000 and 20, 000 years to make just one full orbit around the sun.

Caltech researchers have found evidence of a giant planet tracing a bizarre, highly elongated orbit in the outer solar system. The object, which the researchers have nicknamed Planet Nine, has a mass about 10 times that of Earth and orbits about 20 times farther from the sun on average than does Neptune (which orbits the sun at an average distance of 2.8 billion miles). In fact, it would take this new planet between 10, 000 and 20, 000 years to make just one full orbit around the sun.

The researchers, Konstantin Batygin and Mike Brown, discovered the planet's existence through mathematical modeling and computer simulations but have not yet observed the object directly.

"This would be a real ninth planet, " says Brown, the Richard and Barbara Rosenberg Professor of Planetary Astronomy. "There have only been two true planets discovered since ancient times, and this would be a third. It's a pretty substantial chunk of our solar system that's still out there to be found, which is pretty exciting."

Brown notes that the putative ninth planet—at 5, 000 times the mass of Pluto—is sufficiently large that there should be no debate about whether it is a true planet. Unlike the class of smaller objects now known as dwarf planets, Planet Nine gravitationally dominates its neighborhood of the solar system. In fact, it dominates a region larger than any of the other known planets—a fact that Brown says makes it "the most planet-y of the planets in the whole solar system."

Batygin and Brown describe their work in the current issue of the Astronomical Journal and show how Planet Nine helps explain a number of mysterious features of the field of icy objects and debris beyond Neptune known as the Kuiper Belt.

"Although we were initially quite skeptical that this planet could exist, as we continued to investigate its orbit and what it would mean for the outer solar system, we become increasingly convinced that it is out there, " says Batygin, an assistant professor of planetary science. "For the first time in over 150 years, there is solid evidence that the solar system's planetary census is incomplete."

The road to the theoretical discovery was not straightforward. In 2014, a former postdoc of Brown's, Chad Trujillo, and his colleague Scott Sheppard published a paper noting that 13 of the most distant objects in the Kuiper Belt are similar with respect to an obscure orbital feature. To explain that similarity, they suggested the possible presence of a small planet. Brown thought the planet solution was unlikely, but his interest was piqued.

He took the problem down the hall to Batygin, and the two started what became a year-and-a-half-long collaboration to investigate the distant objects. As an observer and a theorist, respectively, the researchers approached the work from very different perspectives—Brown as someone who looks at the sky and tries to anchor everything in the context of what can be seen, and Batygin as someone who puts himself within the context of dynamics, considering how things might work from a physics standpoint. Those differences allowed the researchers to challenge each other's ideas and to consider new possibilities. "I would bring in some of these observational aspects; he would come back with arguments from theory, and we would push each other. I don't think the discovery would have happened without that back and forth, " says Brown. " It was perhaps the most fun year of working on a problem in the solar system that I've ever had."

Fairly quickly Batygin and Brown realized that the six most distant objects from Trujillo and Sheppard's original collection all follow elliptical orbits that point in the same direction in physical space. That is particularly surprising because the outermost points of their orbits move around the solar system, and they travel at different rates.

"It's almost like having six hands on a clock all moving at different rates, and when you happen to look up, they're all in exactly the same place, " says Brown. The odds of having that happen are something like 1 in 100, he says. But on top of that, the orbits of the six objects are also all tilted in the same way—pointing about 30 degrees downward in the same direction relative to the plane of the eight known planets. The probability of that happening is about 0.007 percent. "Basically it shouldn't happen randomly, " Brown says. "So we thought something else must be shaping these orbits."

The first possibility they investigated was that perhaps there are enough distant Kuiper Belt objects—some of which have not yet been discovered—to exert the gravity needed to keep that subpopulation clustered together. The researchers quickly ruled this out when it turned out that such a scenario would require the Kuiper Belt to have about 100 times the mass it has today.

That left them with the idea of a planet. Their first instinct was to run simulations involving a planet in a distant orbit that encircled the orbits of the six Kuiper Belt objects, acting like a giant lasso to wrangle them into their alignment. Batygin says that almost works but does not provide the observed eccentricities precisely. "Close, but no cigar, " he says.